Together with your colleague Dr.ir. Richard Lopata, you investigate an alternative method for determining the risks of plaques in carotid arteries without surgery. For the laymen among us: what are plaques?

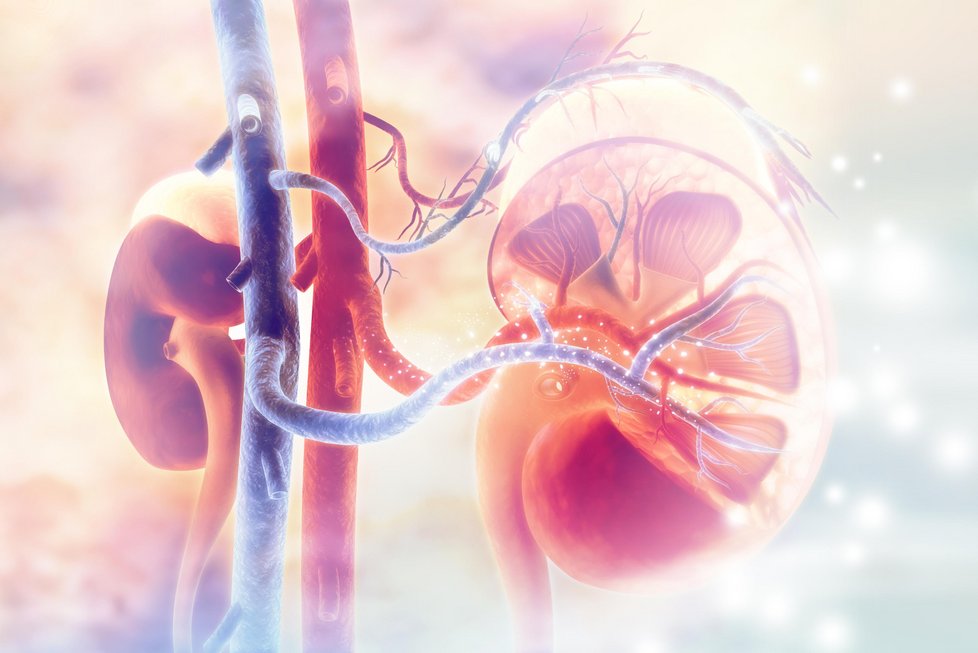

Plaques are accumulations of fat and body cells on the inner wall of arteries. Calcium can also accumulate in the plaques. This is where the Dutch term (slag)aderverkalking [arteriosclerosis] comes from. In this research, we focus on plaques in the carotid arteries. A plaque creates a constriction in the blood vessel which can rupture, causing the contents to come into contact with blood. This can lead to blood clots on the plaque, from which small pieces of clots and sometimes also loose parts of the plaque can be taken to the brain via the blood flow. The possible result is a cerebral infarction.

One is (rightly) rather careful when it comes to plaques in the carotid arteries. This is why a narrowing in the carotid artery is often treated surgically. At the moment, we are not really able to determine which narrowing of the carotid arteries really requires surgery. As a result, we still regularly perform operations that turn out not to have been necessary. In the future, we want to use our research be able to better determine which plaques are a real risk of causing a cerebral infarction (unstable plaque) and which plaques pose little risk (stable plaque).

Your method is non-invasive: you use a hand scanner. Can you explain how this scanner works?

We look at plaques in the carotid artery from two angles: the mechanical properties of the vessel wall and the plaque using functional ultrasound and the composition using photoacoustic imaging. The so-called hand scanner is therefore an ultrasound and a photoacoustic probe. Both examinations are non-invasive; we do not need to perform surgery or inject a contrast agent. As a result, the examined patient does not feel anything and the examinations are absolutely harmless.

Besides being a professor, you are also a vascular surgeon. Your resume is an exceptional list of connections and activities. When or in what role did you get the inspiration for this research?

Before I started working at Catharina Hospital in 2008, I studied and worked for 20 years at the Erasmus MC in Rotterdam. During that period, I was already active in research,including on plaques in carotid arteries. But that research had a clearer clinical character. After I had established myself in Eindhoven, I came into contact again with Professor Frans van de Vosse and saw the possibilities for advanced non-invasive imaging and modeling.

How did you end up working with Richard Lopata?

It very quickly became clear that the scientific interests of Richard Lopata and I were similar. Healthcare is pretty well-organized according to evidence-based medicine. Good scientific research lies at the heart of the current guidelines. This also applies to constrictions and plaques in carotid arteries. The guidelines indicate that a narrowing in the carotid arteries increases the risk of a cerebral infarct. But an increased chance also means that there is still a chance that the cerebral infarct will not occur. As we cannot determine which risk group the patients fall into, they are all operated on – with all the associated risks. Richard and I share the dream of determining the risk group that each patient falls into and thus cutting the number of unnecessary surgeries.

Richard and I have different backgrounds and I think the strength of our research lies in that difference. We combine Richard’s technical expertise with my clinical knowledge and therefore bring the university and the hospital closer together. This offers a lot of possibilities. In our research, we quickly combine preclinical laboratory research with clinical validation.

What practical problems did you encounter in your research? And have you been able to overcome one or more of these?

Photoacoustic is an innovative technique and therefore still in development. We have participated in European research on developing a prototype photoacoustic probe. It worked out well, but it can and should be done even better. This means that we have to develop hardware and software in collaboration with various parties. Sometimes, we think we’ve found the solution, but then it turns out it doesn’t work well enough in practice. We then have to take a few steps back and partially start over. This is sometimes frustrating but always fascinating.

Via the fund, you’ve received a substantial contribution to your research from a donor. Did the donor in question have a personal reason for choosing your research?

The donor is a bequest foundation in Rotterdam and I knew this foundation from my work in Rotterdam. Richard Lopata and I submitted a very substantial research plan which it seems the foundation thought was worthy of funding. I also think that we’ve put ourselves in the spotlight with the combination of ‘technique and clinic’ in our research.

What can you do thanks to this contribution (which you would otherwise have had to leave out)?

Without this grant, we would not be able to carry out the research at all. With this grant, we can do research for six years with a postdoc, two PhD students and a technician/scientist. There is then also money for the purchasing of materials and the development of models.

“University funds are crucial for the university, the scientists and – above all – our society.”

Why do you think that the University Fund is important for scientists, students and education?

The world is calling for solutions to a large number of societal problems, such as energy, the environment, food supply and healthcare. Fortunately, the Netherlands is a knowledge economy and we can make a substantial contribution to those solutions. If we want to guarantee this, we need good educational institutes and scientists. Innovation is the key concept here. Of course, there is public funding for scientific research, but that’s not enough. University funds offer opportunities to tap into other sources and are therefore crucial for the university, the scientists and – above all – our society.